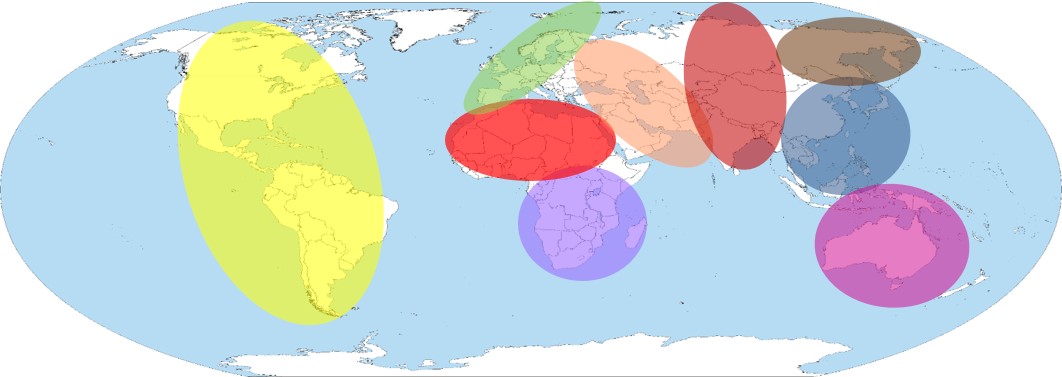

The Geographic Population Structure (GPS) tool is the most accurate tool for predicting recent geographic origin of any world population. The tool was publised in Nature Communications with highlights in Science (Genetic 'App' Tells You Where You're From) and Nature Communications (Genes give clues to where in the World you came from).

My lab has led the development of the tool and will continue developing advanced tools as well as GPS applicaitons for non-humans.

This work was widely covered by the media (see Press).

In Elhaik (2013), we tested the genetic diversity among European Jews in light of the two hypotheses: the Rhineland Hypothesis (the narrative) and the competing Khazarian Hypothesis. The results unambiguously support the Khazarian Hypothesis, portraying the European Jewish genome as a tapestry of ancient ancestries and high heterogeneity. This is the most popular paper published in GBE. It was ranked #1 most-read paper since its publication. This work was widely covered by the media (see Press).

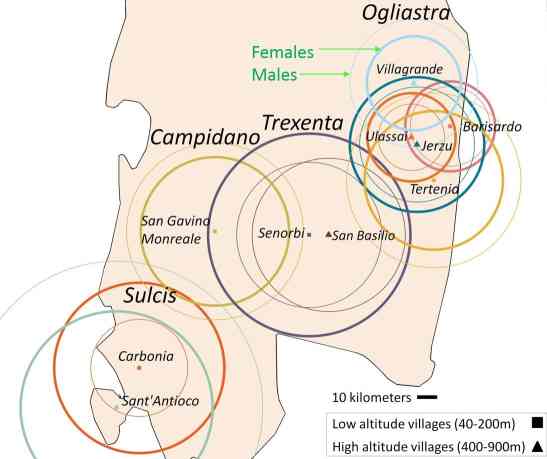

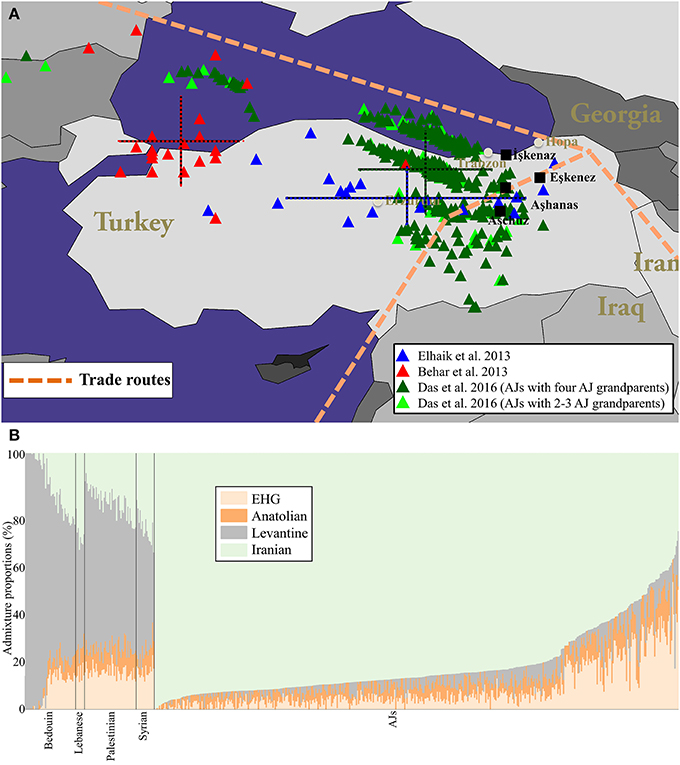

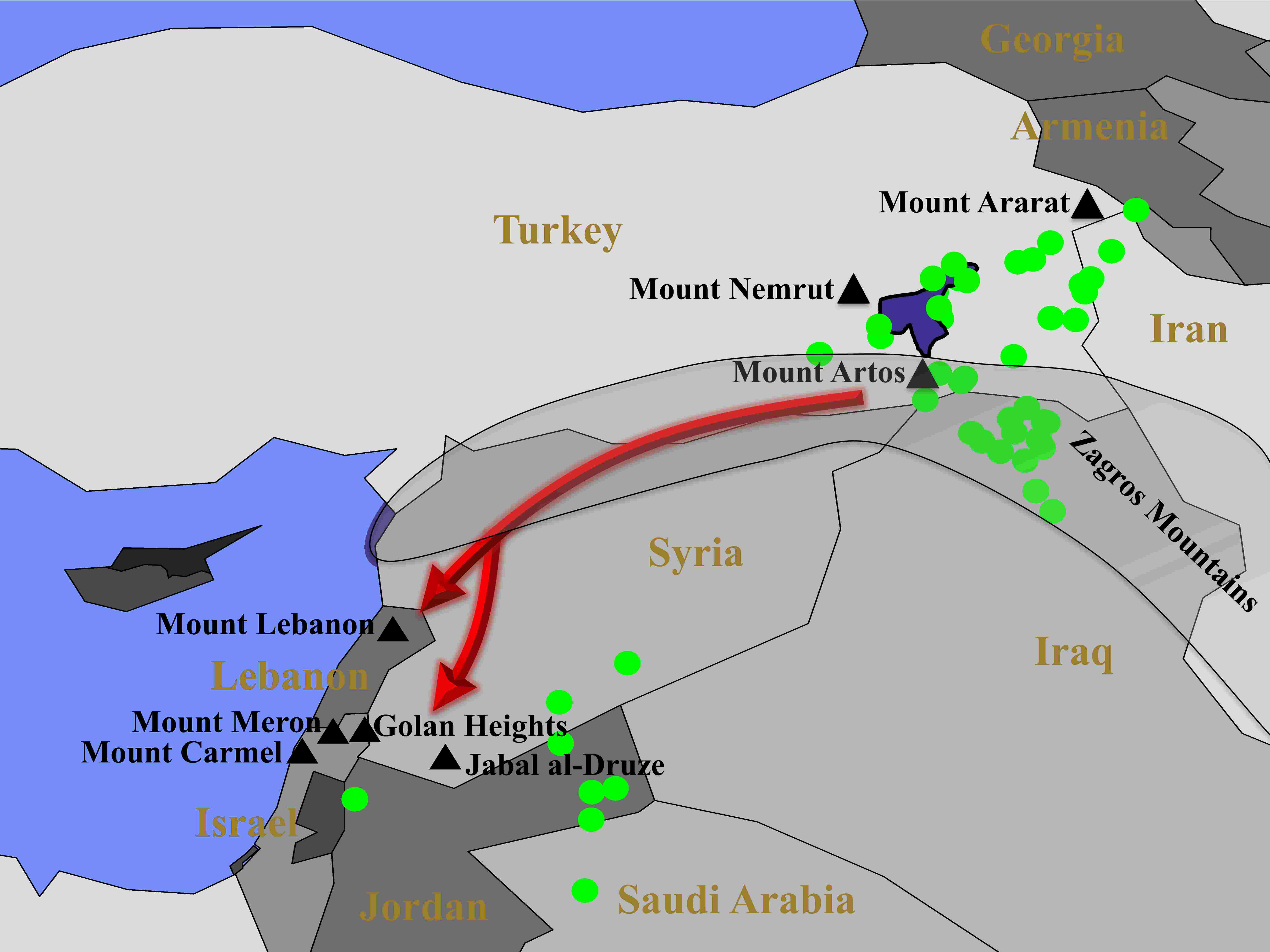

In Des et al. (2016), we aimed to identify the origin of Yiddish. Since language, genetics, and geography are correlated we reasoned that the geographical origin of Yiddish can be derived from the geographical origin of the DNA of Yiddish speaking Ashkenazic Jews. To infer the geographical origin of their genomes, we applied the Geographic Population Structure (GPS) tool to the genomes of over 360 "Yiddish speaking" 180 "non-Yiddish speaking" Ashkenazic Jews. We traced their genomes to northeast Turkey where we uncovered four villages whose name may be derived from the word "Ashkenaz."

The paper was ranked #1 most-read paper in GBE since its publication.

This work was widely covered by the media (see Press).

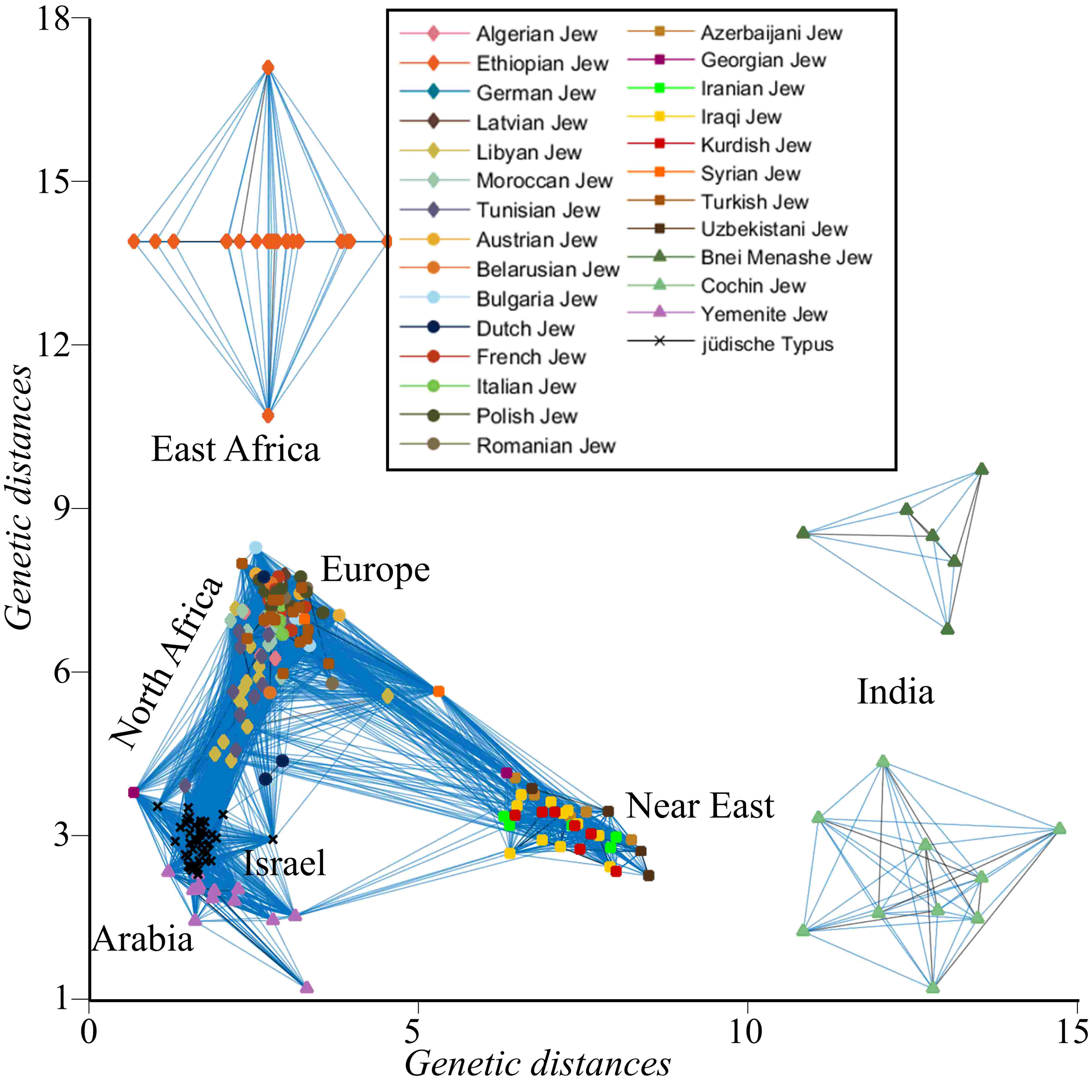

In Elhaik (2016), we questioned claims that there exist Jewish biomarkers. We did that by posing a public "Jewish genome challenge" where scientists, public members, and 23andme were asked to distinguish between Jewish and non-Jewish genomes in a blind setting. All testers have failed. We next compared the genetic distances between Jewish communities and show that they are genetically distinct from each other and from a simulated population of Judaeans (below).

To learn more, see three population science articles that I wrote for: The Conversation, Aeon, and Atlas of science.

In Das et al. (2017), we replied to the criticism of Das et al. (2016). We showed that all biogeographical analyses on AJs identified Turkey as the place of DNA origin and carried out ancient DNA analysis. We also showed that AJs have ancient Irano-Turkish origins and practically no Levantine ancestry.

We confirmed these findings with an ancient DNA by showing that Druze exhibit a much higher similarity to ancient Aremnians than to ancient Levantine populations, as opposed to modern-day Levantine populations that exhibit the opposute patterns.

Our findings were published in here.

I led the development of the microarray and all online tests now used routinly by the Genographic Poject. My lab continues collaborating with the Genographic Project and collaborators in addressing quesitons related to human history, migraitons, admixture, and linguistics.

In (Elhaik et al. 2013), we announced the development of the GenoCh